News

JIANG SHAN CHUN (WANG XIN) COLLECTED BY THE NATIONAL ART MUSEUM OF CHINA (NAMOC)

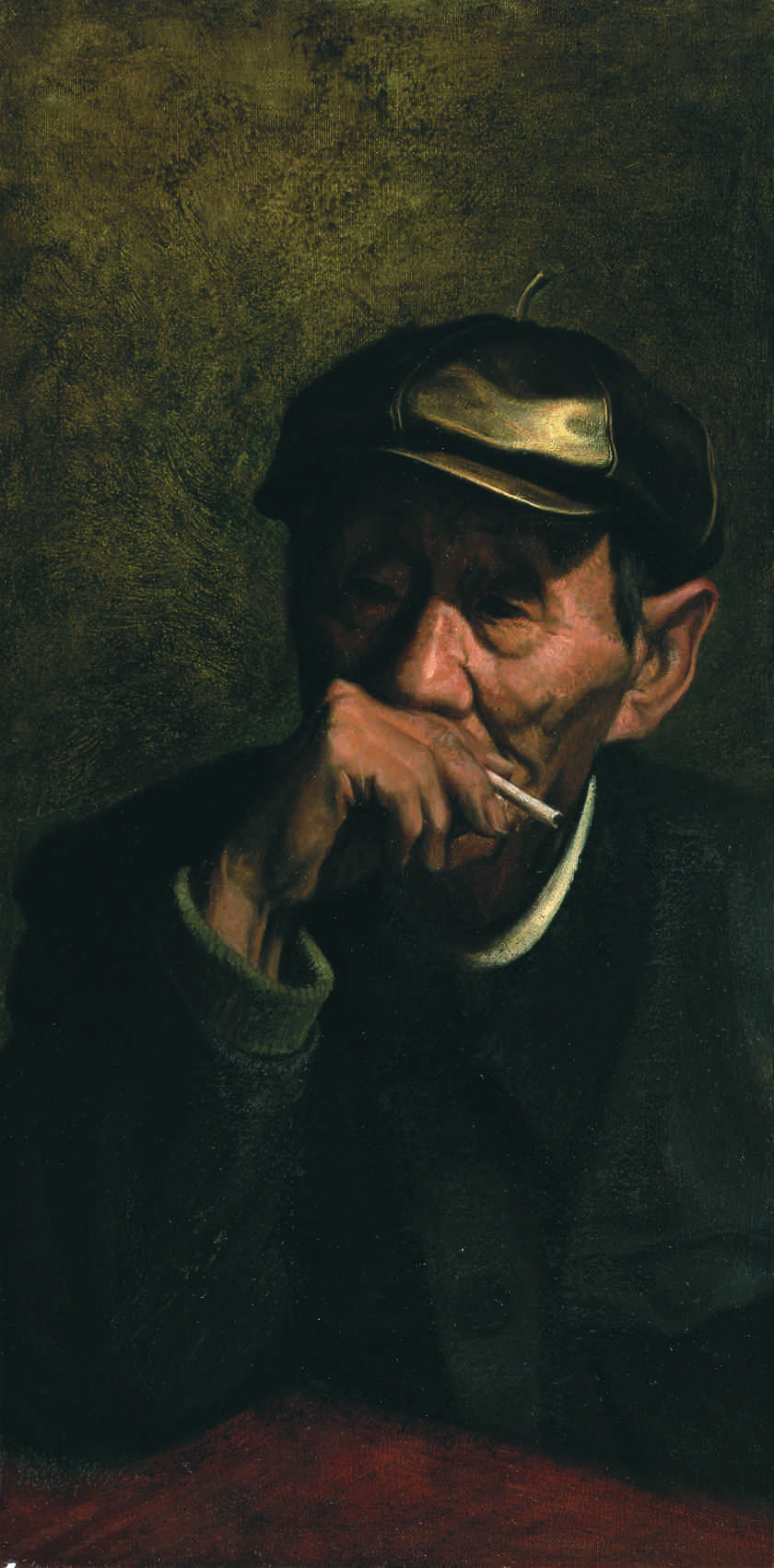

Jiang Shan Chun’s (Wang Xin’s) 2007 Oil on Canvas painting Memory has been collected by the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC).

Memory is emblematic of Jiang Shan Chun’s artistic conviction in depicting what is indigenous, intuitive and distinct to China, notably through his great preoccupation with portraits that are both arresting and understated. Here, as in so many of his portraits, Jiang invites the viewer to skip back into chapters of China’s past and, conversely, to find what is age-old in the present. He demands our un-peeling of the superficial layers of China’s contemporary face, to find deeper signifiers of her culture:- its deep-seated patterns of behaviour, customs and the characters that reveal much more than an all-too-easy homogenized outsider’s view. And it is as if we were entering a process of refutation of time. The concept of refuting time is in fact embedded in Chinese philosophy, originating in Taoism, whereby reversal is the movement of the Tao (“the way”). The possibility of heightening one’s engagement with life through alignment with the Tao and related concepts such as neidan, or “spiritual alchemy” if you will, comes about through physical, mental and spiritual discipline. These processes Jiang seeks to both assimilate in his artistic process and to transmit to the viewer through his art works.

Jiang’s intention, and subsequent aesthetic effect, is a sense of wu wei, “without effort”, or wu wei wu, “effortless action” or “diminished will”, as espoused in Taoism and by Zhuangzi, the influential Chinese philosopher of the 4th century BCE (the Warring States period, an era corresponding to the philosophical summit of Chinese thought— the Hundred Schools of Thought). The aim of wu wei, as prescribed by Taoism, is to achieve a state of perfect equilibrium; similarly, the effect Jiang achieves throughout his work, not only his portraiture, but also his still life and abstract works, is a supreme sense of serenity. Through his philosophy and practically, the masterful way in which Jiang applies traditional techniques, particularly tempera, and tempera mixed with oil, allows an unusual combination of acute realism and muted form. The result, as exemplified in Memory, is at once carefully rendered realistic portraiture and understated atmosphere, devoid of all pretension and affectation, qualifying a return to one’s original being.

Jiang Shan Chun, like many established and burgeoning artists alike working in China today are arguably more interested in uncovering directions where the vital force is not contingent on Westernization, capitalization, material factors; but rather, on traditional Chinese philosophy, enduring stories and the dramatis personae of unposed, uninhibited characters with primal faces, to which the backdrops are at times the rich landscapes, at other times the simple domesticity of China, and to the foreground the backbone of every Empire in history – a vast and fluid population of manual workers.

As the prominent Chinese artist Zeng Fanzhi has observed of his creative interests and artistic practice:

“The unique social circumstances and ideologies enrich the artistic spectrum of contemporary China. While more and more artists pay attentions to societal and political issues, there are also some… who are more concerned with the life experiences of ordinary persons. The former may help remind the observers of the existence of a “Chinese Art,” or “Chinese Contemporary Art,” as in their capital forms. But I am certainly prone to the latter. I have a deep concern with the substantial life experiences of ordinary people.”

– Zeng Fanzhi, in interview with Michael Findlay, ‘Zeng Fanzhi’, published by Acquavella Galleries, 2009, pg. 6

Such subjects and their treatment through traditional Chinese approaches to aesthetic experience distinguish a unique aspect of art practice in China today, and arguably reaches the very core of understanding China’s development:- that contrary to popular Western assumption, rather than the “Westernization” of China, she retains her autochthonous, very traditional ‘heart and soul’.

– E. S. de W. P.